Towards ending immigration detention of children

Migrant children are first and foremost children, and under international law children should never be detained based on their migration status or at all in the immigration context. In the European Union (EU), this principle has been laid down in legislative instruments and policies regarding migrant children, that clearly set out the obligation to avoid any form of detention of children due to their immigration status.

Detention has severe negative impacts on children’s lives, on their mental and physical health and well-being, and has serious long-term consequences. Despite this, in a number of EU Member States children are still being systematically detained for immigration purposes; in many others, children and families with children are subject to coercive measures that restrict their freedoms and largely disregard the best interests of the child.

The International Commission of Jurists (ICJ) and partners (aditus foundation in Malta, Foundation for Access to Rights in Bulgaria, the Greek Council for Refugees, Defence for Children International – Belgium, Helsinki Foundation for Human Rights in Poland, the Hungarian Helsinki Committee and ASGI in Italy) have over the last two years worked together on the CADRE project (Children’s Alternatives to Detention protecting their Rights in Europe) in order to address this situation and to bring the realities for many children closer to the standards required by EU and international human rights law. The overall goal of the project has been to raise awareness amongst practitioners of the international human rights law obligation to use alternatives to detention (ATD) and to refrain from detaining migrant children, and to explore and help put in practice effective and viable rights-based alternatives to detention for migrant children.

Best practice and key outcomes of the project

The project partners agreed from early on that the best practices to be recommended are rooted in case management and the integration of migrant children into mainstream child protection systems. Placing a migrant child in a country’s mainstream child protection system is most likely to result in a high level of compliance with the human rights of the child, protected under international human rights law as well as EU law. These include the rights to family life, education, health, play, and protection against ill-treatment. The UN Committee on the Rights of Migrant Workers and their Families, the supervisory body of the International Convention on the Rights of all Migrant Workers and their Families, understands as ATD all community-based care measures or non-custodial accommodation solutions – in law, policy or practice – that do not involve detention.

The project partners agreed from early on that the best practices to be recommended are rooted in case management and the integration of migrant children into mainstream child protection systems.

At the early stages of the project, the ICJ and partners mapped the existing situation when it comes to detention of children in partner countries. The organisations held three closed expert workshops focusing on different aspects of alternatives to detention for children. Throughout the workshops, participants considered the feasibility of introducing alternatives to detention in national systems, and explored a number of good practice examples from across the EU.

Project partners subsequently convened webinars focusing on the possible challenges and obstacles in implementing alternatives to detention. One webinar also looked into the on-going negotiations about the EU Pact on migration, which also includes recommendations to use alternatives to detention, while introducing mandatory border procedures and not exempting children in all cases. Another webinar looked closely at the EU Child guarantee – a strong commitment by EU Member States towards all children, including migrant children regardless of their status – to secure their rights, such as free healthcare, education, healthy nutrition, and adequate housing.

As an outcome of a series of expert workshops, the ICJ also published a set of Training Materials on Alternatives to Detention for Migrant Children. The first training module covers the international and EU legal framework of ATD for children and related rights. The second gathers specific good practice examples of alternatives, such as case management or placement of migrant children into mainstream child protection systems. Module III details the right to be heard and procedural rights of children, and module IV covers communication with children in this context. The training modules are aimed at national judges, lawyers, State executive authorities, guardians of children, social workers, and other practitioners and are available in six languages (English, French, Dutch, Greek, Bulgarian and Polish).

One particular example of good practice highlighted within the materials is an ongoing pilot project for families in Belgium (Plan Together: towards durable solutions) which is implemented by the Jesuit Refugee Service Belgium, a member of the European Alternatives to Detention Network. The project offers community-based alternatives to detention to families with children, supporting them on a legal, social and psychological level to work towards a sustainable future. The project starts with screening and selection and involves initial basic actions to build trust, regular home visits, monthly team meetings with the immigration office, legal screening, individual plans of action, impact assessment, and ultimately case closure. Regular home-based counselling stands in place of and prevents a deprivation of liberty of the family.

The ICJ and partners have also created a case-law database with national case-law from Poland, Bulgaria, Greece, Malta and Belgium, as well as relevant international law sources and case-law. Short summaries of each case can provide a snapshot of the case-law in another EU country and may serve to provide inspiration and useful sources for their own litigation work.

Throughout the second phase of the project, national partners launched the publication of training materials nationally and have held trainings for various practitioners in five EU Member States. Over two hundred people were directly trained or involved in advocacy meetings, module launches, and discussions. There seems to be more and more awareness of the need to address the issue of detention of migrant children and to implement non-coercive, engagement-based alternatives to detention. The project results have created important tools for lawyers and other experts in the field and are expected to make a significant contribution towards ending immigration detention of children.

Written by Karolína Babická (Legal Adviser, International Commission of Jurists – Europe and Central Asia Programme). The ICJ implemented the CADRE project (Children’s Alternatives to Detention protecting their Rights in Europe) from 2021-2023, aimed at promoting the end of child migrant detention in Europe. You can find here the training materials and case-law database created as part of the project.

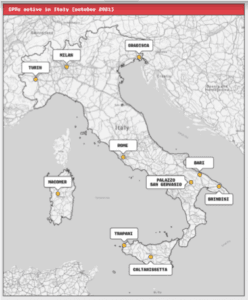

Today, Italy runs 10 CPRs in Turin, Milan, Gradisca d’Isonzo, Rome – Ponte Galeria, Palazzo San Gervasio, Macomer, Bari, Brindisi, Trapani and Caltanissetta. Over the past three years, these centres have cost Italian taxpayers upwards of 44 million euro. Further to this overwhelming financial burden on Italian society, this money has largely gone in the pockets of private companies managing CPRs across Italy. During this period, the average expenditure to detain one person was around 1000 euros per day. For a detention centre that holds 400 people, this means a cost of 40,150 euros per day. This represents a staggering waste of public money, which only benefits the for-profit companies that administer CPRs. For them, depriving people on the move of their freedom and dignity, is a business that has become a

Today, Italy runs 10 CPRs in Turin, Milan, Gradisca d’Isonzo, Rome – Ponte Galeria, Palazzo San Gervasio, Macomer, Bari, Brindisi, Trapani and Caltanissetta. Over the past three years, these centres have cost Italian taxpayers upwards of 44 million euro. Further to this overwhelming financial burden on Italian society, this money has largely gone in the pockets of private companies managing CPRs across Italy. During this period, the average expenditure to detain one person was around 1000 euros per day. For a detention centre that holds 400 people, this means a cost of 40,150 euros per day. This represents a staggering waste of public money, which only benefits the for-profit companies that administer CPRs. For them, depriving people on the move of their freedom and dignity, is a business that has become a