“Black Holes”: CILD’s report reveals human rights violations in Italy’s immigration detention centres

In late 2021, the Italian Coalition for Civil Liberties and Rights (Coalizione Italiana Libertà e Diritti Civili, CILD) published its first ever report on Italy’s immigration detention centres – Black Holes: Detention without charge in Repatriation Centres for Migrants – Centri di Permanenza per i Rimpatri (CPRs).

This report provides extensive analysis of the conditions experienced by those held inside Italy’s 10 immigration detention centres (CPRs), where people are deprived of their liberty for months on end. The experience of detention is akin to imprisonment, but without the guarantees and due process offered by the criminal justice system, and without any evidence of those detained presenting any threat to public safety. Furthermore, despite the fact that the Italian Government and the private entities managing the centres are obliged to ensure respect for the human dignity of those detained, the reality is that fundamental rights within CPRs are either neglected or completely denied. There is also a concerning lack of transparency and accountability, with very little information about these centres made public.

In this context, “Black Holes” intends to provide an overview of the current state of affairs regarding immigration detention in Italy, including insight into the origin and nature of CPRs, as well as the living conditions experienced by people in detention. CILD examines the need for protection of fundamental rights, exposing a number of suicides, deaths, and episodes of self harm that have taken place in CPRs in recent years. The report also includes data on the economic costs of CPRs, as well as information about their management.

CILD’s aim in publishing this report is to shine light where there is none, where there are no spotlights or cameras – places that would truly be black holes if community and civil society organisations did not work to uncover the truth of what happens within them.

Alongside the report, CILD has launched a website dedicated to immigration detention issues, which showcases interviews with the report authors and other experts.

Administrative Detention in Italy: A Background

Immigration detention in Italy dates back more than two decades. Introduced in 1998 as a “non-criminal” detention practice, its purpose was to hold foreign or third-country nationals prior to their repatriation for as long as necessary in order to enable identification and expulsion procedures. Since then, immigration detention has been a constant element in Italian migration management policies, more recently legitimised by the European Union with the introduction of the Return Directive of 2008.

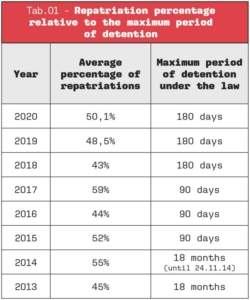

CPRs were established with the introduction of the Turco-Napolitano Law. While the maximum detention period was initially set at 30 days, it gradually increased – first to 60 days (Law no.189/2002), then to 180 days (Law no. 125/2008) and, finally, to 18 months (Decree-Law no. 89/2011). Since 2011, time limits have once again decreased – with a brief rise as a result of the so-called “Salvini Decree” from 2018 to 2020 – and currently the maximum limit for immigration detention is 90 days.

While the time limit for immigration detention has varied considerably over recent years, the same cannot be said of repatriation rates which have remained consistently low. Given that the facilitation of return is one of the main stated aims of detention in Italy, these low rates put into question the use of detention as a migration management policy. In fact, as noted by the National Guarantor for the Rights of Persons Deprived of their Liberty (National Guarantor), it appears that the effectiveness of detention in ensuring repatriation remains steadily low regardless of the length of detention. Moreover, these consistently low rates suggest that detention is in fact an ineffective tool to facilitate returns. As shown in the below table, the rate of repatriation of those in detention in 2020 was 50.1%; in previous years it has remained relatively steady, never going above 59%.

The ineffectiveness of Italy’s return policy is even more obvious if we consider the figures for the total number of repatriations, including not only people held in immigration detention centres but also those pushed back at the border or forcibly accompanied to the border in Italy. According to data provided by the National Guarantor, 3,351 people were repatriated in 2020 out of 517,000 undocumented migrants present in Italy. Considering these numbers, the National Guarantor has affirmed that it is time to rethink administrative detention as a whole, rather than seeking to individually resolve the numerous shortcomings of the detention estate in a piecemeal way.

Immigration Detention Centres and Fundamental Human Rights

While the effectiveness of the Italian Government’s migration governance already indicates a need to rethink the systematic use of immigration detention, for CILD the core concern lies with the erosion of freedom and dignity that accompanies the detention system, and the various and compounding situations of injustice experienced by those who are detained.

In “Black Holes”, CILD documents a number of illegal practices taking place in immigration detention centres, particularly regarding detention conditions. For example, the report draws attention to the complete lack of assessment of migrants detained in the centres, despite requirements for the judicial authority to determine the impacts that detention might have on each individual depending on their specific circumstances and vulnerabilities. Ninety percent of the immigration lawyers interviewed by CILD stated that in most cases there is no certificate of eligibility for detention in the judicial authority’s files. In addition, provisions for the right to health within CPRs are not of an adequate standard. Healthcare is managed by private entities which are entrusted to the managing entity of the centres, not to the National Health Service. In such conditions, the detention of those with serious physical, mental or emotional health needs is entirely inappropriate.

With respect to the right to information and defence, the report reveals that people detained are not consistently provided the right to participate in hearings regarding their own detention. Further, such hearings are meant to determine the validity or extension of a person’s detention, and typically last a questionable 5 to 10 minutes. Several critical points were also identified in CILD’s research concerning the appointment of lawyers, as well as the unreliable timing of communications to lawyers regarding legal hearings related to their client’s detention. For instance, in some centres, people in detention are prevented from communicating with their lawyers until the validation hearing has already taken place. According to a number of lawyers interviewed by CILD, this unlawful practice is intended to essentially provide a rubber stamp for validation procedures, with little regard for the facts of individual cases: “not having a trusted lawyer who knows the history of the individual detainee and who also has the possibility to produce a series of defensive documents, makes the whole validation process of the Justice of the Peace much faster [and] much more streamlined.”

The findings of “Black Holes” show that CPRs are places where people who have been deemed “guilty of travel”, but of no actual crime, are cruelly deprived of their personal liberty and their basic fundamental human rights.

The 44 Million Euro Price Tag of the Immigration Detention Estate

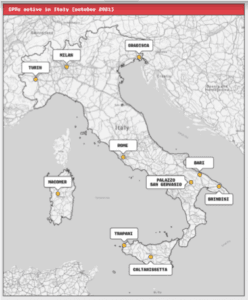

Today, Italy runs 10 CPRs in Turin, Milan, Gradisca d’Isonzo, Rome – Ponte Galeria, Palazzo San Gervasio, Macomer, Bari, Brindisi, Trapani and Caltanissetta. Over the past three years, these centres have cost Italian taxpayers upwards of 44 million euro. Further to this overwhelming financial burden on Italian society, this money has largely gone in the pockets of private companies managing CPRs across Italy. During this period, the average expenditure to detain one person was around 1000 euros per day. For a detention centre that holds 400 people, this means a cost of 40,150 euros per day. This represents a staggering waste of public money, which only benefits the for-profit companies that administer CPRs. For them, depriving people on the move of their freedom and dignity, is a business that has become a “very profitable supply chain.”

Today, Italy runs 10 CPRs in Turin, Milan, Gradisca d’Isonzo, Rome – Ponte Galeria, Palazzo San Gervasio, Macomer, Bari, Brindisi, Trapani and Caltanissetta. Over the past three years, these centres have cost Italian taxpayers upwards of 44 million euro. Further to this overwhelming financial burden on Italian society, this money has largely gone in the pockets of private companies managing CPRs across Italy. During this period, the average expenditure to detain one person was around 1000 euros per day. For a detention centre that holds 400 people, this means a cost of 40,150 euros per day. This represents a staggering waste of public money, which only benefits the for-profit companies that administer CPRs. For them, depriving people on the move of their freedom and dignity, is a business that has become a “very profitable supply chain.”

The reality is that Italy’s immigration detention centres are truly black holes, where basic human rights are violated in secret, without transparency or accountability. These places are also legal black holes, as numerous principles that form the very foundation of Italy’s domestic and international legal system are breached with impunity on a regular basis.

Over the past three years, these centres have cost Italian taxpayers upwards of 44 million euro. Further to this overwhelming financial burden on Italian society, this money has largely gone in the pockets of private companies managing CPRs across Italy.

Black holes such as this are a stain on our society’s respect for human life, dignity and due process, and it is not only those who are detained who suffer, but also their families and entire communities. It is in the interest of all citizens and the people of Italy to demand that inhumane, oppressive and excessively costly detention does not continue in our name. There are proven and effective alternatives to managing migration that ensure dignity, humanity and freedom, while also prioritising the growth and future of our society as a whole. These alternative solutions can help Italy overcome this failing administration detention system, which seems more necessary now than ever before.

Written by Flaminia Delle Cese (Legal and Policy Officer, Coalizione Italiana Libertà e Diritti Civili). CILD is a member of the International Detention Coalition and the European ATD Network. Along with Progetto Diritti, CILD runs a pilot ATD project in Italy providing holistic case management to migrants to risk of detention. Find out more here.